Estimated Reading Time: 17 minute, 57s.

Here are two things that we know about smartphones:

- The more time we spend on them, the worse our mental health. (More on this in a bit.)

- Smartphones are a necessity of modern life.

These two ideas are annoyingly incompatible with one another.

After switching from an iPhone 14 Pro smartphone to an old-fashioned flip phone for a month, I repeatedly noticed this. If you want to get to the takeaways from the experiment, scroll down a bit—but I also want to share the story of how this experiment came to be.

The impetus for this experiment began following a moment of frustration that I still remember vividly. A couple of years ago, I was traveling home from a work retreat. On the train that connects Toronto’s airport and train station, sitting calmly and comfortably in my seat, I started looking around. At the time, it was the rare moment I didn’t have headphones stuck in my ears; instead, people-watching, I soaked in the hustle and bustle of the airport commuter traffic. There were 20 or so people in my train car, and every single one of them was tapping, scrolling, and swiping around on their phone. This didn’t bother me a ton: most of us have gotten used to this zombiefication phenomenon by now. (Plus, we’ve all got stuff to do and people to connect with all day. Strangers deserve some slack and some credit.)

What bothered me, though, was how not one person in the train car looked happy. Every single one of the 20 people had a zoned-out expression on their faces. Half of me felt frustrated with the whole scene. The other half wanted to give everyone a hug.

Noticing how bummed people looked, I pulled my own phone out of my pocket, feeling its smooth stainless-steel edges and glassy front and back with my hand. This was the first moment I began questioning the role the shiny device had in my life—and thinking about the role it deserved to have.

Fast-forward a couple of years, past many similar moments of people-watching… well, people watching their phones, this frustration boiled over. My approach to using my smartphone has always been to contain the distraction and to define boundaries around when I use the device to save time and defend my attention. This has worked for developing my focus. But over time, I became increasingly frustrated with the device and how it made me feel. I also didn’t enjoy much of the time I spent on the thing.

That’s when I decided to switch to a flip phone for a month. As I’ve found in the past, sometimes pushing an idea to its logical extreme can lead to some unexpected lessons. And also, I was curious about what I’d find.

Here’s a countdown of the top 5 lessons I learned in a skimmable list format in case you’re pressed for time—or attention.

5. The more screen time you get, the worse your mental health

- This connection is especially robust if you’re under 18 years old

- The link between screen time and depression is significant, regardless of your age

You probably don’t need this reminder—especially if you have the attention span to make it this far down in the article—but you should know that the research on screen time is conclusive: the more time you spend on your smartphone, the more likely it is to be harmful to your mental health. This is true for all ages—and it’s especially true if you’re under 18.

Consider that three separate meta-analyses1 found that:

- For kids and adults, the more screen time you get, the worse your “dietary behaviours, sleep, mental health, physical health, and eye health.”2

- For adults, our amount of screen time predicts depressive symptoms.3

- For kids, higher screen time usage is associated with depression, obesity, calories consumed, a less healthy diet, and an overall reported lower quality of life.4

The smartphone is not always bad: this research obviously doesn’t mean the device is pointless. But at the end of the day, the correlation stands: the more screen time you get, the worse your mental health. If you’re like me, you may not need scientific evidence to know this: you can think back to how your life has changed since getting a smartphone.

This leads to the conundrum I mentioned at the top of the article: while our phone is not good for our mental health, it’s necessary to function and communicate with others in the modern world.

4. If you don’t like your phone, reflect on exactly what you’re unhappy with

- If you’re unhappy with your phone, you’re probably not unhappy with every single thing about the device

- Find precisely what’s bothering you about the device: it might be easier to fix than you think

Having a smartphone can be considered a necessity of modern life—and you’re expected to have one to communicate with others.

Here’s a thought experiment for you: Imagine your relationship with your smartphone was an actual relationship in your life. Is it a good one?

For a lot of us, the answer is no. (The more screen time you get, the more likely the same is true for you.)

Some of the best progress I made in changing my relationship with my smartphone happened when I reflected on what I was unhappy with. This is an obvious lesson worth sharing, if only because I hadn’t thought about it before the experiment: If you aren’t generally happy with your smartphone, you should reflect on what you’re unhappy with.

The modern smartphone provides us with a collection of experiences—some of which make us happy, some that make us depressed, and many that are merely a shallow source of mental stimulation.

If you’re anything like me, and your phone doesn’t bring you the joy it used to, it probably isn’t a wholly bad presence in your life. For example, maybe instead of being unhappy with your phone, you’re dissatisfied with:

- Your mind’s stimulation level when you use the device;

- The amount of time you spend on the thing; or

- The stable of apps you gravitate to when you have some free time—which make you far less happy than you think.

I was most unhappy with the phone because it meant I was expected to communicate with everyone I knew in a shallow way. I also deleted a couple of apps that weren’t making me happy. Stepping back let me shape my smartphone—I deleted apps that weren’t serving me and made a more concerted effort to up the level of communication richness in my days.

If you’re unhappy with the time you spend on your phone, that’s worth reflecting on. Maybe the reason is obvious and staring at you in the face. In my case, it wasn’t as apparent as I initially thought.

3. Communication can be far richer (even if getting there takes effort)

- On the smartphone, we typically gravitate to communicate in ways that are less sensory-rich

- Look for opportunities to make communication in your life richer

Technology has fused with how we communicate—to the point where, as the saying goes, the medium has become the message. When technology fuses with communication, the simple presence of that technology shapes how we communicate and can make communication more artificial.

There are countless ways we can communicate via our smartphone, which vary from sensory-rich forms like talking over FaceTime or the phone to shallow forms like texting or sliding into someone’s direct messages on social media. I have personally always defaulted to what’s simple and asynchronous, spending more time communicating in shallower ways simply because it has been easier. With all the options available, some richer than others, I gravitated to what was quick, efficient, and shallow.

Getting rid of my smartphone automatically eliminated many of these shallow ways of connecting. (I could still access some from my iPad.)

As the month progressed, I started craving connection with others in a way that I haven’t in a while. I also quickly began to carve out far more time for the people in my life—in person. It was oddly refreshing not to have any technology mixed up with how I communicated with friends.

This is not always a bad thing: this same tech lets us communicate with anyone around the world in a fraction of a second. But when real face time (not FaceTime) is the alternative, this fusion has downsides. Over time, since getting a smartphone, my communication style has become more about speed than richness. Because I can connect with anyone, instantly, I’ve always felt as though my innate need for socialization has been met.

Including when it hasn’t. Sure, I could connect with anyone on the planet at any moment, but at the expense of not connecting with the person right in front of me: the coffee shop barista, a stranger on the bus, or sometimes even the friend sitting across from me at the restaurant.

At its best, communication is sensory-rich.

We have the communication culture we do—but as I found, we must try to enrich how we communicate with others. Since starting the experiment, I’ve attempted to do this more. When a friend has suggested a video call, I’ve suggested coffee or lunch instead. When I find myself sending a lot of short messages with someone, I’ll pick up the phone to call them instead. Not everyone has wanted to switch over to something richer—and sometimes I find I have the same aversion myself. But getting over this social anxiety to make communication richer has made a meaningful difference in my life—the richer the communication has become, the richer my days feel.

When we leave richness on the table, we also leave meaning on the table.

2. Mind when you hand off your attention to someone else

- We often hand our attention over to someone else for them to guide us through an experience

- We must do this deliberately and thoughtfully

In my book Hyperfocus, I write about how we often hand our attention over to a third party to guide us through some experience. For example, if you choose to watch a movie, you hand your attention to the movie’s director to guide you through a (hopefully) banger of a blockbuster. Similarly, if you choose to play a video game, you hand your attention over to the game’s designers to guide you through a series of challenges and rewards, with a healthy amount of feedback sprinkled in.

We also regularly hand control of our attention to the phone apps we use.

Over time, it has become increasingly difficult to use technology intentionally. After leaving a movie in a theatre, we feel satisfied. Yet, time on our phone seems to always leave us wanting more.

There’s a reason for this. Our experiences in the digital realm are usually very novel—and this novelty leads to the release of dopamine in our brain. Dopamine doesn’t lead us to feel happy and satisfied in and of itself—it leads us to feel as though pleasure is right around the corner, so it keeps us wanting more. The more novel an app, the more we get hooked—we feel a constant rush and keep using the app until we remember to stop. (Here’s looking at you, TikTok.)

Some apps are delightful to use and provide us with an experience similar to how a movie does: we hand off our attention and then enjoy ourselves. Just think of Netflix or YouTube. But, unfortunately for us and our attention, the smartphone has introduced some perverse incentives into the mix. Because many app developers—including most social media app creators—make more money the more time we spend in-app, they have an incentive to keep us hooked. As I write about in How to Calm Your Mind, we now live in what can be considered an Era of Novelty. When so much of what we pay attention to on our phone is dripping with novelty, the most instinctual part of our mind doesn’t want to put the device down.

Sometimes when we use our phone, novelty is all we’re after.

Intentions slip from our grasp.

Our attention is perhaps the most powerful mental resource we have for living deeply and intentionally while also getting things done. For this reason, it’s critical that we see our attention as something we own; something we can deploy with grace, wisdom, and purpose. Notice when you hand off this incredible faculty of your mind to someone else—especially if you’re doing so for a novelty fix. There are great experiences to be had in handing your attention over to someone else, from Broadway musicals, to binge-watching marathons, to Super Bowl Sundays.

But on our phone, we must question why someone wants our attention. Notice when you’re happy and satisfied after using your smartphone —and when you’re left wanting more.

For some reason, there are lessons we have to learn multiple times before they eventually stick. Even after writing How to Calm Your Mind and Hyperfocus, this is one for me: the state of our attention determines the state of our lives. We must manage this faculty of our mind wisely, noticing when we hand it off to others.

1. Deeper happiness is found at lower levels of mental stimulation

- Generally speaking, the number of novel (dopamine-fueled) activities we engage with every day determines our mind’s “stimulation height”

- Lowering our height of stimulation makes us more focused, creative, and productive

Just because something stimulates your mind doesn’t mean it makes you happy. Often the exact opposite is the case.

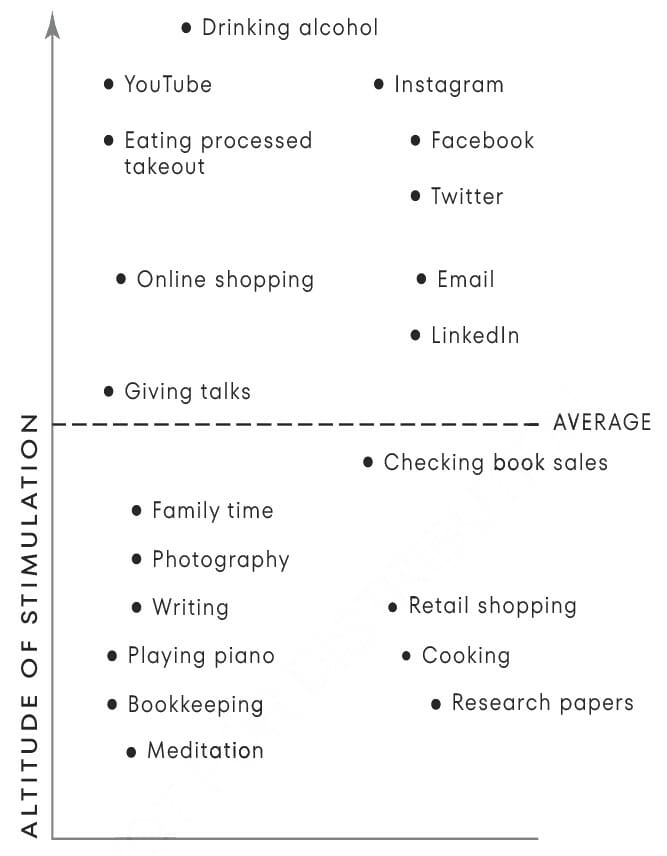

In my most recent book, How to Calm Your Mind, I write about how everything we pay attention to throughout the day has a different “altitude of stimulation,” depending on how novel it is to us. Simplified, the activities that make up our day hover around different levels of stimulation because they vary in how much dopamine they lead to the release of. Here’s a photo of this idea pulled from the book featuring some of my tasks:

Our brain needs time to acclimate to a new, lower stimulation level. But once it does, we feel calmer and less anxious while deepening our focus. This roots us into the moment, making us more focused, engaged, and productive. We can cultivate focus and presence with whatever we’re doing and whomever we’re with. It’s quite nice. And we have more attention for the world around us. The higher our altitude of stimulation, the less attention we have—which makes us feel we also have less time.

On the experiment’s first day, I checked in on the flip phone often. I grew restless, missing the hits of novelty and stimulation. Eventually, this mental fidgeting gave way to calm as I settled down to a new stimulation level. Our mind’s stimulation level is determined by the altitude of activities we engage with on a given day. Not having a smartphone significantly lowered my daily average, though it took adjustment at first.

The higher we fly, the less we want to come down to the activities that lead us to become productive, accomplished, and satisfied with how we spend our time. But we need to do this more. The flip phone experiment essentially served as an accidental stimulation fast—where we go without the most stimulating parts of our day for a while—simply because of how many of the most stimulating parts of my day came from that one device.

It took about a week to settle downward to the new level.

If you decide to do a similar fast—a topic I’ll be covering more on the site soon—I’m confident you’ll find that coming down worth while—and worth the effort.

Happiness is found at lower levels of mental stimulation.

The Ending

Three weeks into the experiment, a family member I’m close with got sick—she was going in for cancer treatment and was at the point of telling family about it. With my iMessages all wonky, I didn’t know what updates I was missing—and ended up missing two or three updates about her that I later heard about from somebody else. At that moment, driven equal parts by guilt and frustration, I thought screw it, and popped the SIM card back into my iPhone to see what else I had missed. It was a hard snap back to reality as old iMessages came flooding in. (Oop, there goes gravity.)

Around this same time, more amusingly (at least to me), my wife was also starting to field messages meant for me. My friends and family were beginning to message her, instead of me, because they still couldn’t reach me over iMessage.

It quickly became apparent that the smartphone is not designed to be switched away from, especially perhaps if your phone is an iPhone—designed around features like iMessage that Apple uses to lock in its users.

I didn’t realize it at the start of the experiment, but pulling my SIM card out of my iPhone and sticking it in a flip phone (first the Alcatel Go Flip 3, and then the far-better Punkt MP02) was the equivalent of throwing a grenade into my Apple walled garden ecosystem paradise.5) iMessage conversations instantly turned against me—at a certain point, I stopped receiving all iMessages, including on devices I had the Messages app installed on, like my iPad. My Apple Watch no longer had a buddy iPhone to sync to, so I couldn’t look at the health data my watch was recording. My AirPods no longer worked with the phone I walked around with. The list of annoyances and challenges goes on. And on. And on and on and on and on.

With the grenade lobbed into my walled garden, I was missing a lot more than I expected.

Racking my brain about how to keep the experiment going while fixing these issues, I realized something: I’m an adult. (I forget this often.) In other words, I can eat popcorn and ice cream for dinner simply because I have the inclination to. And if I wanted to, I could end this impractical experiment and go back to living my damn life without the frustrations of having an old-timey flip phone in the year 2023.

At this point, I switched back to my smartphone for good.

Having a flip phone in 2023 is unfortunately not that realistic. I wish it were, kinda. In my opinion, communication used to be a hell of a lot better, and richer. As a result, time felt richer as well. I remember snacking out of the bins at the Bulk Barn store in University with a few friends until we got caught and they put our photos up on the wall. I also remember meeting my wife and connecting with her instantly after locking eyes with her from across the hall. I can’t say that I have similar memories over Zoom. Or an even less rich form of communication, like texting.

The smartphone is not a perfect device—very far from it. And I’m not convinced that mine makes me happy. The screen time research seems to agree with me on this point. But while modern communication methods are shallow, at the end of the day, the smartphone is how I am able to communicate with those I love in the modern world. And I love them. So I will continue to go where they are, to these lamely shallow apps that are no richer than a shadow, especially when compared to the vivid, textured reality of deep, joyous time with another human being, in real life. Maybe over coffee, maybe over drinks, maybe at a beach somewhere. Honestly, wherever—I don’t really care. As long as it’s in person.

In my opinion, flip phones suck more than smartphones. But at this point, we’re stuck with smartphones, especially considering how intertwined they are with how we communicate. Technology will continue to advance as smartphone innovation continues to plateau, and eventually, something else will take the smartphone’s place.

I look forward to this day, and hope that whatever replaces the phone doesn’t come with its own tradeoffs for our mental health and overall well-being.

The key, though, while the smartphone is with us, is to find ways to limit its downsides while making how we communicate richer.

Notice your impulses. Notice when you turn to the empty hits of stimulation. And center how you use your phone around the value the thing brings to your life.

I hope you find your days are far richer as a result.

For the uninitiated, a meta-analysis is a study that summarizes the current research about a topic. ↩

Source: Changes and correlates of screen time in adults and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis – PubMed ↩

Source: Screen time and depression risk: A meta-analysis of cohort studies – PMC ↩

Source: Effects of screentime on the health and well-being of children and adolescents: a systematic review of reviews | BMJ Open ↩

For the uninitiated, an ecosystem is when your devices are made by the same company (whether Apple, Google, Microsoft, etc.), so they work together in various helpful ways. Lock-in is when it’s a challenge to get out of this ecosystem because it’d be such a pain to switch, or you’d have to give up features (like iMessage, FaceTime, “Sign in with Apple,” etc.) to do so. This is where the whole “walled garden” idea comes from—once you’re in the ecosystem, it gets increasingly difficult over time to get out. (You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave. ↩